When are D-graded neighborhoods not degraded?

Greening the legacy of redlining

Abstract

This paper explores how geography shapes the legacy of redlining, the systemic mortgage lending bias against minority us neighborhoods. On average, redlined neighborhoods lag behind adjacent, less-discriminated areas in home values, income, and racial composition. Yet, redlined neighborhoods near parks and water fare better. To help understand convergence, we inventory waterfront renovations, apply machine learning to historical imagery to track tree canopy changes, and instrument such changes exploiting tree replacements due to geographic variation in tree plagues and susceptible species. Findings suggest that enhancing waterfronts and increasing tree canopy can mitigate the long-lasting effects of institutionalized discrimination.

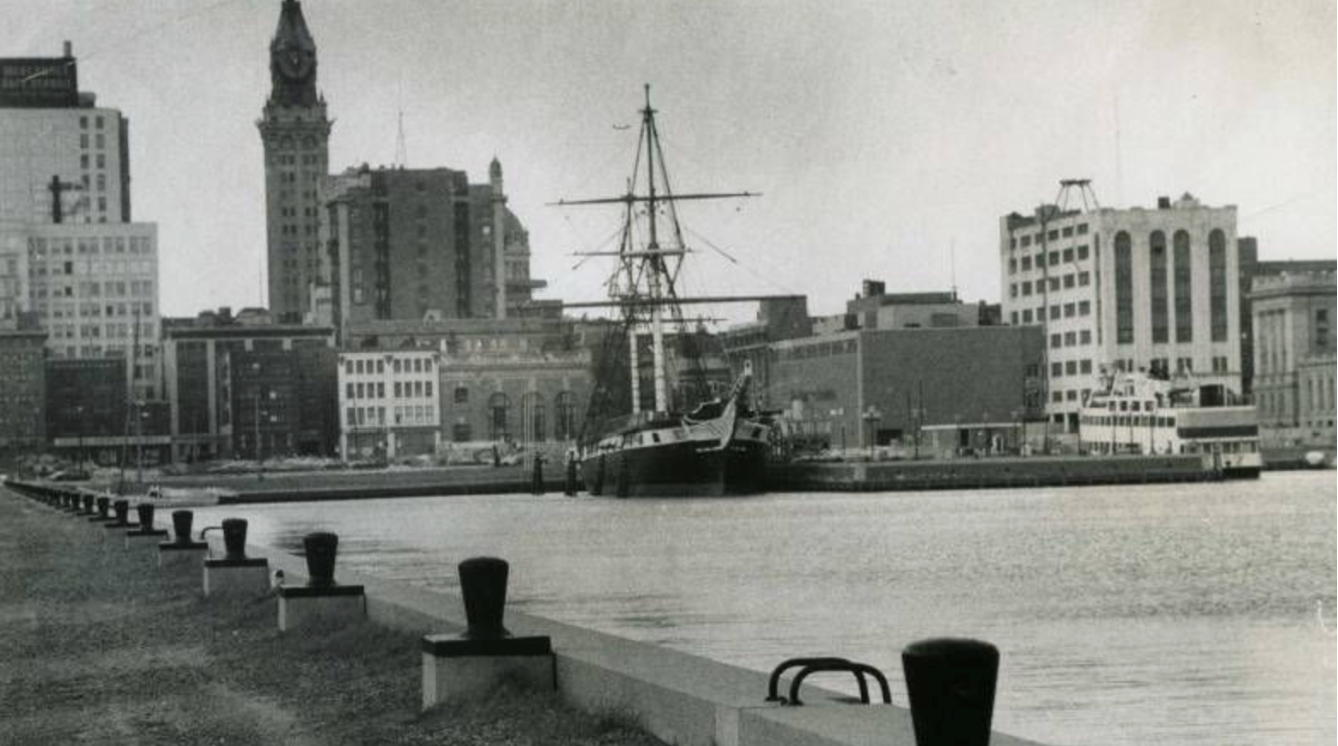

The Baltimore Inner Harbor example

From his home near the Inner Harbor, C.J. Welsh has watched with interest the new building that has transformed the downtown area and the renovation that has made his neighborhood one of the most expensive and sought in the city. […] “I used to live in a 12,000$ row house in South Baltimore”, said Welsh. “Now I live in a 40,000$ town house on Federal Hill, and I haven’t moved”. (The Washington Post, 1984)

Suggested citation

@misc{minano2023,

author = {Alba Miñano-Mañero},

title = {When are D-graded neighborhoods not degraded? Greening the legacy of redlining},

year = {2023}

}